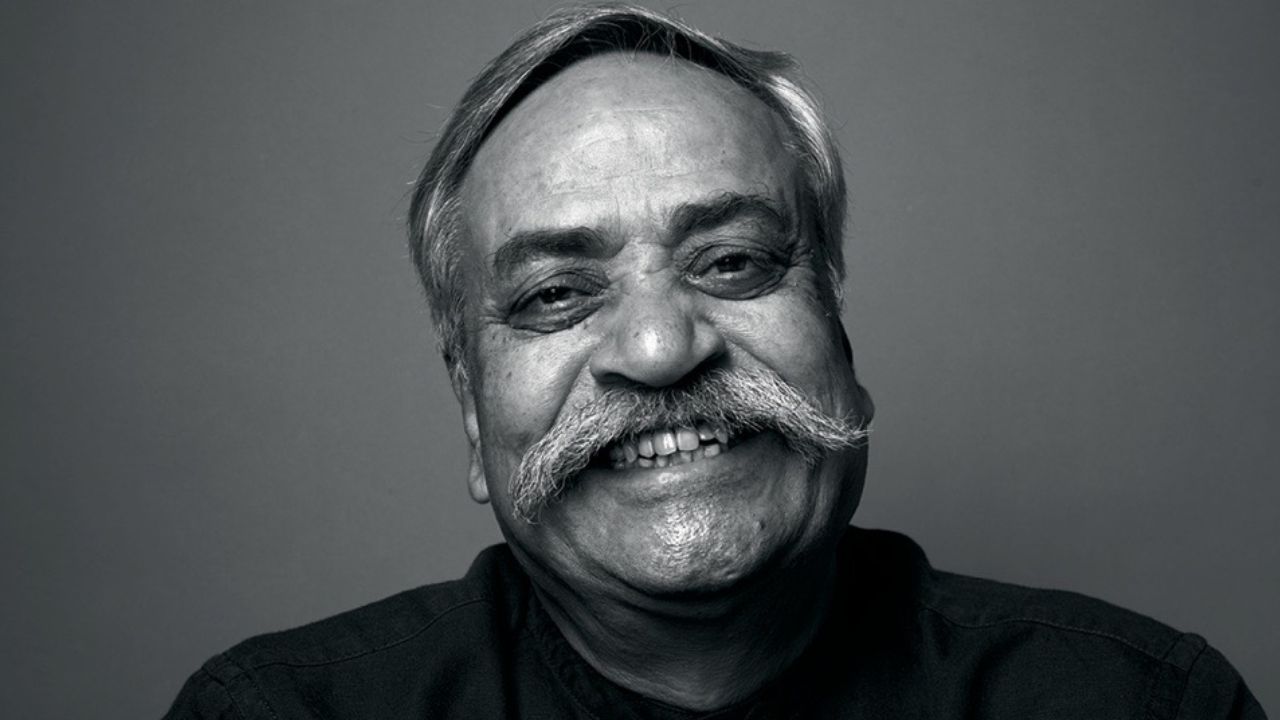

Piyush Pandey, global chief creative officer, Ogilvy, kick-started the fireside chat by posing a question about how to create an identity for yourself, or a brand? He said, “As they say, products are made in factories, but brands are made in the hearts of people.” He requested Sutherland to share his thoughts with young Indian entrepreneurs.

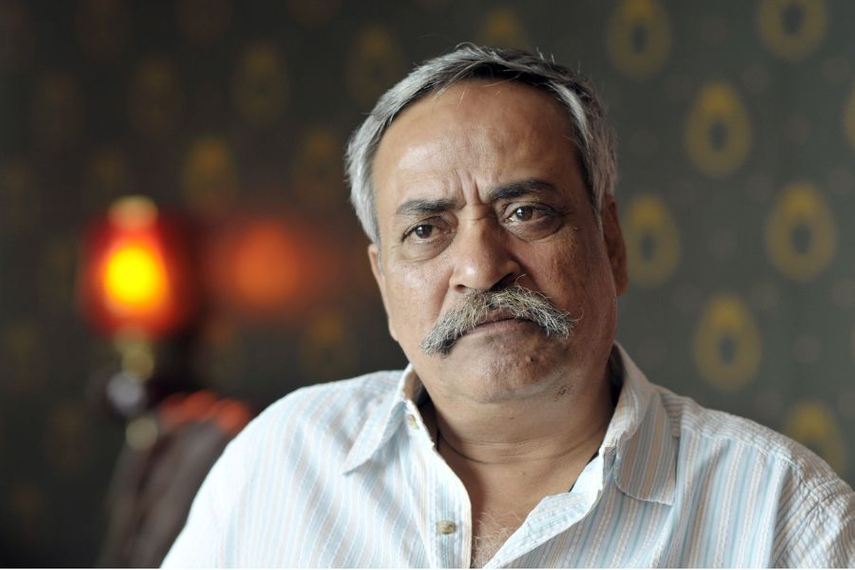

Rory Sutherland, vice chairman, Ogilvy UK, pointed in the direction of early 20th century trends in the United States. He said, “We often tend to think of the factories as what drove it, but actually the United States became an economic powerhouse, in part, on the back of the mail order industry.”

Sutherland said, at one point, Sears and Montgomery Ward accounted for 25% of US retail sales. “What's interesting is, if you look at Byron Sharp’s idea of mental and physical distribution, they’re both necessary before you can either build out at scale and enjoy efficiencies of scale, or before you can enjoy gains to specialisation which is selling something which is a niche product, but to a geographically distributed audience.”

He stated, “People who think about distribution and manufacturing always underestimate the importance of mental distribution. But equally, those of us in the advertising industry probably underestimate the importance of physical distribution, which is just getting the stuff on the shelves.”

Sutherland said, “By creating this extraordinary distribution network within India, Amazon has done something in the space of very few years, which is akin in importance to what Montgomery Ward did, or what Sears did for the United States.”

Creating a personality about your brand

Pandey cautioned the Smbhav delegates about the misconception of “reaching out to so many people through technology.” He said, “What each one of us should remember is that reaching people is not good enough. Reaching people with a message that stays with them is what is required.” He added, “Reaching somebody is not good enough, it’s like distributing visiting cards to a million people.”

Sutherland concurred with Pandey. He quoted from a book by the market researcher John Cohen “Until a character becomes a personality, it cannot be believed, and without personality, a story cannot ring true to the audience”.

Sutherland said, “Until you’ve created some sort of personality around your product, which is building enough trust and belief to be willing to stump up the money in the first place, without that, you’ve got nothing.”

He said people are sceptical about this notion, since most “economics tends to take demand as a given.” Sutherland expanded his proposition by stating, “Have a look at economics as a discipline, any marketer will find economics alarming as a discipline, because it starts from the presumption that the consumer has perfect information and perfect trust, and proceeds from that. Economics has nothing to say about how you create that trust in the first place, but without it, you’ve got nothing.”

Sutherland shared an example of Starbucks. He said there was nothing in market research, or much in consumer behaviour that said Starbucks would succeed. No one was walking around the United States in 1993 saying ‘Why can’t I spend USD 3.50 on a cup of coffee?’

Sutherland said, what made Starbucks interesting “is that when you focus on selling only one thing, consumers tend to assume that you're pretty good at that thing. Previously, coffee had always been sold as an adjunct to something else. You bought soup and a coffee or a sandwich and a coffee, or in the United States, you went into a gas station, and happened to pick up a coffee.” In addition, Starbucks built a brand through huge distribution. They opened stores and created a certain amount of self-advertisement.

Pandey concurred with Sutherland and said advertising has “a very narrow definition”. He said Starbucks success was determined by people carrying those cups, with a lot of badge value. Pandey said, “So where do you jot down the expense in your ledger books — advertising spend, or experience spend, or direct marketing spend or any other spend?”

Advertising strategy for B2B

Next, Pandey and Sutherland discussed B2B advertising. Sutherland said, “When we think about b2b advertising, we think about narrowing the target audience and defining them very narrowly down to their job title and a particular business sector.”

He cited the example of social media influencers. He said, we look at them and we say you’ve got a terrible approach to life. You should try and get rich by doing something brilliantly, and then get famous on the back of that. But today’s generation is trying to get rich by getting famous first.

Sutherland felt, perhaps this generation is right. Kids aren't right. “That if you’re famous, opportunity comes knocking.” He added, “If you’re more famous as a B2B brand, you’re suddenly discovering markets and clients and customers out there that you never envisaged when you were defining your target audience more narrowly.”

He shared a tip with the audience. He said, “One of the great reasons to advertise is not just to measure your advertising, by how successfully it achieves what you intended it to do. …That always underrates the value of advertising, you’ve also got to measure the value of your advertising and what it achieves that you never intended.”

Sutherland shared an example. He said, “If you’re a famous company, whenever your chief executive rings someone up, they call back. If you’re the chief executive of Rolls Royce Aero Engines, you can call anybody on the planet and they’ll return the call. If you’re the chief executive of XYZ enterprises, that doesn’t happen.”

Piyush Pandey shared two other B2B examples from India: Asian Paints, and Pidilite (the makers of Fevicol). He explained how they’re more B2C than any brand can dream of being. He said, “Because they became famous in the streets before they became famous in the hearts. They did the kind of things that made them famous and then they went out to talk to consumers.”

Sutherland said, “The idea of just get famous for something, and then see what happens’ probably isn’t the bad strategy. It’s more probabilistic, rather than deterministic and it doesn’t look very strategic, but that doesn’t mean it should not work.”

Building a long-term brand

Pandey said, “I would love to see India making brands, brands that first go national, hopefully they go global, hopefully they’re able to attract a lot of money into this country, which we can invest back into other things where we require the money.”

He added, “Our first aim should be to become national, most of our brands are not even national, let's try and be national and then be international.” He said, “A lot of Indian companies are present in South Asia, are present in parts of Africa or parts of South America. For example, the motorcycle businesses of Bajaj and Hero are big in these areas.”

Pandey asked, what is global? “Global means more than 150 countries? Or does it mean one brand is travelling outside one country and being attractive in more countries?” He requested Sutherland to discuss the “biggest of brands” McDonald’s. How the global brand was actually a regional or local brand at the outset.

Rory Sutherland alluded to the fact that the United States a company of regional brands. He said, “You’d have brands that were only known in the southwest, brands only in the northeast. Historically, Pepsi was Northern and Yankee and Coke from Atlanta was Southern. Now, nobody thinks of it like that anymore. But actually, that's how most of these brands started. They started regional and then with national distribution and national media, there was a kind of fight to be top dog.”

He added, “It may play out differently for the regional brands in India. But it’s not a bad principle to try and be national before you go global.”

He stated, “India has huge potential to create national luxury brands.” He made an important point about India having a big advantage since it has not “over-invested in manufacturing, because manufacturing is kind of a race to the bottom. You already see China being undercut by Vietnam.”

He explained, “All these manufacturing powerhouses realise is that the money is made by the brand owner, by the person who puts a final stamp of approval on the manufacturing product. That isn't really in manufacturing.”

In this sense, he felt the presence of Amazon in India is important, because it will have “the same effect that the railways had in the United States.” This, Sutherland felt, applied globally, because through the Amazon site one can access local crafts. “I was looking at the blue and white pottery available on Amazon. I can see a pretty massive market for that in the UK, once people just become more confident in ordering from overseas,” he said.

He highlighted the importance of the interconnected network. He said, “It's worth remembering, there are networks like train networks and air networks, where your proximity to a hub affects the value you derive from that network. If you're close to a global airport, doing global business is much easier than if you're 150 miles from the nearest major airport. If you're close to a rail hub, like Atlanta, or Chicago, it used to be a huge advantage in your business. Now the internet and the postal network aren't like that. The interesting thing with postage and distribution, the interesting thing with the internet is, once you're on the network, it delivers its value pretty equally, regardless of your geographical location. And that's why there is potential for India to become a major services and expertise export market, even more so than it already is. Because, you can add value to a service industry, without your location mattering one little bit.”

The environmental message

Sutherland said, “One solution to making the world more environmentally-friendly is to get people to pay more for less.”

He said, “We become richer, we don't go from drinking a quarter a bottle of Johnnie Walker Red a day to two bottles a day. What you do is you migrate people to Johnnie Walker Black. In a way, you have to remember that when people are paying for intangible value, that is, for a meaning, rather than substance, it's very environmentally-friendly.”

He added, “Typically, twice as much product uses twice as much carbon.” But product + extra meaning and you're getting people to pay more money for intangibles and less for tangibles.

Sutherland said, “That's called dematerialisation.” He shared how it’s already happened to the UK economy. He said, “The UK economy was the first to industrialise. However, in 2006, before the financial crash, it was interesting because the UK reached ‘peak stuff’. Now, I'm not suggesting that the developing world is going to reach ‘peak stuff’ for a while, there are a lot of people who are short of stuff. But ultimately, the solution, unless you want to destroy the planet completely; is for people to spend less on things and more on what they mean.”

Piyush Pandey agreed with Sutherland. He said, “Producing fantastic quality ‘stuff’ at a premium price is something India could do brilliantly well.” He felt, this is where the opportunities lie for the future. Otherwise, we can again fall into the trap that China fell with Vietnam and India has suffered with Bangladesh on textiles.”

He added, the day an economist can define joy, that's the day I'll start listening to the economist.

Sutherland agreed with Pandey. He said, “The assumption of economics is that you start with perfect information about how much utility you'll derive from a product. So, it treats advertising as external to the model. Therefore, people tend to see advertising as a cost, because it's something that you have to pay for.”

Sutherland shared an example. He said, “The Austrian School of Economics thought this was absolute rubbish. They have a great phrase, there's no useful distinction to be made in a restaurant between the value created by the man who cooks the food, and the value created by the man who sweeps the floor. By the man who sweeps the floor, they mean advertising and marketing. There's the product itself and the context, which allows you to enjoy its consumption and they're both interconnected. The money you make from them is equal; it doesn't matter whether you're an innovator. There are two ways you can innovate, you can either find out what people want, and find a really clever way to make it or you can work out what you can make and find a really clever way to make people want it. They're both profitable; it doesn't matter in which direction you do it.”

Piyush Pandey shared the Haldirams case study. “The two Haldiram brothers from Rajasthan said that this savoury product is manufactured from chickpea flour. But how about we make it from a lentil which is grown in Rajasthan? And today they are giving a run for the money to international fast food joints.”

Sutherland said, but here’s where you have got to play “very carefully”. He said Indian retail is slightly different from Western retail. If you make it too fancy, people assume they're getting a bad deal. He stated, “Funnily enough, we found the same thing in the UK that one of the problems with making a store. If you revitalise a ‘Tesco’ to be brand new with fantastic flooring and new lighting, people just assume the prices have gone up, even if they haven't.”

Sutherland added, “Obviously, they're always going to be little local subtleties, but understanding how people interpret information subconsciously, is really important. But I think, the way in which they've done those stores is really interesting, because, you know, I think the same thing has happened with fast food in the West. McDonald’s and KFC realised that people's expectations of cleanliness had generally risen. What was acceptable as a food outlet 10-15 years ago wasn't anymore. So, all these things are continually changing because we judge the world against expectation, not by reality.”

When asked about a great rule about how to innovate, Sutherland shared a conversation with a Silicon Valley entrepreneur. Sutherland said, “Do look at all the assumptions in a category and make a list of everything that everybody in the category assumes is true. And then ask yourself, which of those assumptions either isn't true, or won't be true in two year’s time? Now assume that more people are working from home and future more of the time. Okay, so a whole bunch of assumptions about where you want to locate a lunchtime sandwich bar may have to change.

Advertising as popularity and fame, and not as a cost

Rory Sutherland concluded by saying, “Simple advertising is entertainment. Sometimes, the advertising industry gets too clever for its own good because it's always trying to, you know, pick up a highly fashionable approach. But Paul Feldwick in the UK has just written a book called, Why does the Peddler Sing? He makes the point that you can go back hundreds and hundreds of years, and people who sell things have always entertained. It seems so banal; you'll know this having worked on the Vodafone campaign with the pug ads with animals in it. It’s such a banal observation that those of us in the ad industry feel embarrassed. That is, going to a client and say, ‘yes, I know you're an enormous billion-dollar corporation. But don't forget the value of an animal. It's a deep human truth. And let’s not be embarrassed by it.”

Piyush Pandey added, “If there are a billion dollars to be made, there are only nine emotions out of which you can touch one and make another 500-million more.”

Pandey said, “At the end of the day, make a great product, and then touch people’s hearts and make them buy it. That's what I would love to leave behind today.”

Both Rory and Pandey final comments were, “Look (and re-look) to national distribution. Never ignore the opportunity that's on your doorstep. And then look at the potential for building significant Indian brands for export not only to the diaspora, but to everybody and everyone.”

Sutherland signed off by saying, “You know, in the UK, you've converted us to your food already! There's plenty more work to be done.”

(This article first appeared on Printweek.in)